Greetings in Christ Jesus, our Shepherd!

I come to you as your brother who serves you and is deeply committed to our constitutional mandate: “the Bishop is entrusted to maintain, protect, and defend the continuity of the Gospel and Catholic Tradition and to foster the unity of the Body of Christ. This ministry is built upon the three charisms of: teaching, leading, and sanctifying. Therefore, the role of the Bishop is exercised in personal, collegial, and communal ways to witness to and safeguard the unity and apostolicity of the Church."[i].

And so my service to you is one rooted in the preaching of the Good News, assuring an uninterrupted connection to our Catholic tradition and safeguarding our unity in faith and relationship to one another in Christ.

Our Diocese is embarking upon what may first appear to be uncharted waters in a process of discernment and discovery of our future direction in communion with like-minded churches. This is a historical moment as we will select and call forth one from among us along with those to whom we aggregate with locally who will serve as our Bishop. This historical moment in our Diocese is not uncharted but, in fact, clearly given to us in Sacred Scripture, our Catholic tradition and the current Constitution and Norms of our Diocese. My desire is to reflect with you the Church’s story in its earliest centuries about the vital participation and voice of each person in the selection of bishops and to strongly encourage you to look to our own Diocese’s moment in its story. In my ministry to you as bishop, I am concerned that we undertake this process with fidelity to our Catholic tradition and embrace of our Constitution’s letter and spirit.

Recognizing its need for leaders, the early Christian community elected them from its members. Thus, by casting lots Matthias was chosen to replace Judas[ii]. The Seven, traditionally regarded as the first deacons, were also elected, though we do not know exactly how[iii]. None of the earliest ministers of the Church was a bishop in the sense that we understand that office today. St. Paul described a variety of ministries that eventually evolved into the offices of priest and bishop. Those terms were used interchangeably in the New Testament to mean those in charge of a particular church. The Pastoral Epistles to Timothy[iv] and Titus[v] dating from the latter part of the first century, set forth qualifications for presbyters and bishops, but used those terms without distinguishing one from the other. Later liturgical and conciliar texts often refer to the Pastoral Epistles as the ideal to which bishops should aspire. Leadership of local churches by groups of presbyters or bishops gradually gave way to the single jurisdictional episcopate that appeared at least in Asia Minor at the end of the first century, as evidenced by the letters of St. Ignatius of Antioch (d. c. 107). Anicetus became the first official jurisdictional bishop in 154 C.E. From there the idea of ministry by one bishop gradually spread throughout the Christian world.

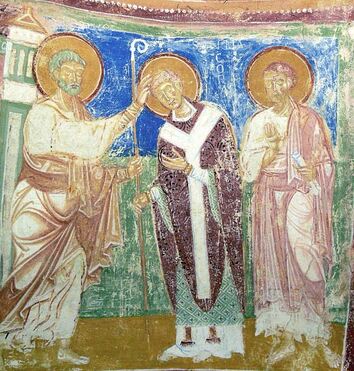

Early liturgical texts testify to the election and ordination of bishops. The Didache or The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, of the second century, states: “You must, then, elect for yourselves bishops and deacons who are a credit to the Lord, individuals who are gentle, generous, faithful, and well tried.” In the early third century, Hippolytus of Rome, in his Apostolic Tradition, asserted that, “The one who is ordained as a bishop, being chosen by all the people, must be irreproachable.”

In the middle of the third century St. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage in North Africa (d. 258) emphasized that, by virtue of divine authority, the bishop should be elected by all the faithful and, that the provincial bishops, after consenting to the election, should ordain the one elected[vi]. He added that the people “have the power either of choosing worthy priests and of rejecting unworthy ones” [vii]. Speaking of the election of Cornelius as bishop of Rome, Cyprian remarked: “Cornelius was made bishop by the judgment of God and His Christ, by the testimony of almost all the clergy, by the vote of the people who were present, and by the college of mature priests and good people” [viii]. The inspiration of the Holy Spirit sometimes prompted a spontaneous election, as in the instance of St. Ambrose who was elected bishop of Milan in 373. Though some elections were contentious, most were probably without incident. In these early centuries, the nominations and elections of bishops were done solely by a popular vote of all the faithful. St. Cyprian believed elections prevented unworthy persons from becoming bishops. By the middle of the third century, however, evidence shows that women were beginning to be excluded from the voting.

In the early fifth century Celestine I (422-432) stated emphatically: “no one who is unwanted should be made a bishop; the desire and consent of the clergy and the people and the order is required”[ix]. Not many years later Leo I the Great (440-461) declared: “the one who is to be head over all should be elected by all” [x]. He also stated: “When the election of the chief priest is being considered, the one whom the unanimous consent of the clergy and people proposes should be put forward . . . It is essential to exclude all those unwanted and unasked for, if the people are not to be crossed and end by despising or hating their bishop. If they cannot have the candidate they desire, the people may all turn away from religion unduly”[xi]. These fifth century bishops of Rome, Celestine and Leo condemned any attempt to impose a bishop without popular consent. Yet, there were attempts in this era to prevent the ordinary laymen from voting and restrict it only to the wealthy and powerful.

By the end of the sixth century, with the rise of feudal bishops and seeing the Church's flourishing wealth and power, secular rulers desired to influence the selection of bishops. Participation by the laity and clergy in the selection of bishops began to erode dramatically.

The witness and wisdom of the ages is self-evident and indicative for our path together as a Diocese. Our current Constitution firmly assents to our Catholic tradition and mandates our honor of it: As a consequence of the basic human right of participation in self-governance, all Catholics have the right to a voice in decisions that affect them, including the choosing of their leaders, and a duty to exercise those rights responsibly [xii].

We can be easily distracted from the treasure of our Catholic tradition and its witness by the ways of our North American culture of corporate business. Corporate process is composed of a number of people who are used to interview candidates for a position. It is a classic task of a search committee to search through resumes and conduct interviews for the position of executive director or CEO. In this model three candidates are the result of sifting through all applicants. Those three candidates are then presented to the board of directors, who chooses one for the job. This is not our model in the Synodal Catholic Diocese of the Southeast. We are synodal [xiii], which requires that the three voices of laity, clergy and bishop(s) come to consensus in major decisions, such as the choice of Bishop. Our Diocesan Norm 67 calls for a wide vote that includes as many of the faithful as possible to elect a bishop. We need to exercise our right and responsibility to prayerfully discern and name candidates to be considered for the election as our next Bishop. Without your informed and conscientious participation, any process for such will be flawed because it is not faithful to our synodal life in communion with one another. Active participation in the process helps to determine the sensus fidelium [xiv] of our Diocese and its communion with others. Let the people speak!

We are best a Local Church when all three voices of our synodal life are speaking and working together. It is then that the Holy Spirit reveals Herself in all that we need to continue on our journey together in communion.

With gratitude to God for you, I remain faithfully yours, in Christ.

_______________________

[i] Constitution 2.2.J.iii

[ii] Acts 1:15-26. Before the election of Matthias "Peter stood in the midst of the believers and spoke to them," and "they proposed two men" (Acts 1:18, and Acts 1:23).

[iii] Acts 6:1-6. In regard to the election of Stephen, "The twelve gathered all the disciples together" and instructed them to "choose seven men from among you full of the Spirit and of wisdom." "What they [the twelve] said pleased the whole community..." (Acts 6:2,3,5)

[iv] 1 Timothy 3:1-7; 5:17-19

[v] Titus1:5-9

[vi] Epistle 67

[vii] Epistle 67.3

[viii] Epistle 55.8. Cyprian understood the electoral process to include four dynamic components: the "judicium" (judgment: choice or selection of candidates), the "testimonium" (testimony about the worthiness of candidates), the "suffragium" or election, and the "consensus," or acceptance. The "judicium Dei" (judgment of God) required both the "judgment of the bishops" and the "judgment of all." (Fitzgerald, 1998)

[ix] Epistolae 4.5, PL 50:434-35

[x] Epistolae 10.6 PL 54:634

[xi] Epistolae 14.5, PL 54:673

[xii] Constitution 1.12.B.vi

[xiii] Constitution 4

[xiv] “Sense of the faithful,” an understanding of what the Christian people believe, accept, and reject. It is here, the sensus fidelium, wherein resides the promise of Christ to protect us from error with the guidance of the Spirit. Bishops have taught what to believe, accept, and reject, but always with acceptance or a corrective response by theologians and the faithful even from the very beginning. (Acts 15)

I come to you as your brother who serves you and is deeply committed to our constitutional mandate: “the Bishop is entrusted to maintain, protect, and defend the continuity of the Gospel and Catholic Tradition and to foster the unity of the Body of Christ. This ministry is built upon the three charisms of: teaching, leading, and sanctifying. Therefore, the role of the Bishop is exercised in personal, collegial, and communal ways to witness to and safeguard the unity and apostolicity of the Church."[i].

And so my service to you is one rooted in the preaching of the Good News, assuring an uninterrupted connection to our Catholic tradition and safeguarding our unity in faith and relationship to one another in Christ.

Our Diocese is embarking upon what may first appear to be uncharted waters in a process of discernment and discovery of our future direction in communion with like-minded churches. This is a historical moment as we will select and call forth one from among us along with those to whom we aggregate with locally who will serve as our Bishop. This historical moment in our Diocese is not uncharted but, in fact, clearly given to us in Sacred Scripture, our Catholic tradition and the current Constitution and Norms of our Diocese. My desire is to reflect with you the Church’s story in its earliest centuries about the vital participation and voice of each person in the selection of bishops and to strongly encourage you to look to our own Diocese’s moment in its story. In my ministry to you as bishop, I am concerned that we undertake this process with fidelity to our Catholic tradition and embrace of our Constitution’s letter and spirit.

Recognizing its need for leaders, the early Christian community elected them from its members. Thus, by casting lots Matthias was chosen to replace Judas[ii]. The Seven, traditionally regarded as the first deacons, were also elected, though we do not know exactly how[iii]. None of the earliest ministers of the Church was a bishop in the sense that we understand that office today. St. Paul described a variety of ministries that eventually evolved into the offices of priest and bishop. Those terms were used interchangeably in the New Testament to mean those in charge of a particular church. The Pastoral Epistles to Timothy[iv] and Titus[v] dating from the latter part of the first century, set forth qualifications for presbyters and bishops, but used those terms without distinguishing one from the other. Later liturgical and conciliar texts often refer to the Pastoral Epistles as the ideal to which bishops should aspire. Leadership of local churches by groups of presbyters or bishops gradually gave way to the single jurisdictional episcopate that appeared at least in Asia Minor at the end of the first century, as evidenced by the letters of St. Ignatius of Antioch (d. c. 107). Anicetus became the first official jurisdictional bishop in 154 C.E. From there the idea of ministry by one bishop gradually spread throughout the Christian world.

Early liturgical texts testify to the election and ordination of bishops. The Didache or The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, of the second century, states: “You must, then, elect for yourselves bishops and deacons who are a credit to the Lord, individuals who are gentle, generous, faithful, and well tried.” In the early third century, Hippolytus of Rome, in his Apostolic Tradition, asserted that, “The one who is ordained as a bishop, being chosen by all the people, must be irreproachable.”

In the middle of the third century St. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage in North Africa (d. 258) emphasized that, by virtue of divine authority, the bishop should be elected by all the faithful and, that the provincial bishops, after consenting to the election, should ordain the one elected[vi]. He added that the people “have the power either of choosing worthy priests and of rejecting unworthy ones” [vii]. Speaking of the election of Cornelius as bishop of Rome, Cyprian remarked: “Cornelius was made bishop by the judgment of God and His Christ, by the testimony of almost all the clergy, by the vote of the people who were present, and by the college of mature priests and good people” [viii]. The inspiration of the Holy Spirit sometimes prompted a spontaneous election, as in the instance of St. Ambrose who was elected bishop of Milan in 373. Though some elections were contentious, most were probably without incident. In these early centuries, the nominations and elections of bishops were done solely by a popular vote of all the faithful. St. Cyprian believed elections prevented unworthy persons from becoming bishops. By the middle of the third century, however, evidence shows that women were beginning to be excluded from the voting.

In the early fifth century Celestine I (422-432) stated emphatically: “no one who is unwanted should be made a bishop; the desire and consent of the clergy and the people and the order is required”[ix]. Not many years later Leo I the Great (440-461) declared: “the one who is to be head over all should be elected by all” [x]. He also stated: “When the election of the chief priest is being considered, the one whom the unanimous consent of the clergy and people proposes should be put forward . . . It is essential to exclude all those unwanted and unasked for, if the people are not to be crossed and end by despising or hating their bishop. If they cannot have the candidate they desire, the people may all turn away from religion unduly”[xi]. These fifth century bishops of Rome, Celestine and Leo condemned any attempt to impose a bishop without popular consent. Yet, there were attempts in this era to prevent the ordinary laymen from voting and restrict it only to the wealthy and powerful.

By the end of the sixth century, with the rise of feudal bishops and seeing the Church's flourishing wealth and power, secular rulers desired to influence the selection of bishops. Participation by the laity and clergy in the selection of bishops began to erode dramatically.

The witness and wisdom of the ages is self-evident and indicative for our path together as a Diocese. Our current Constitution firmly assents to our Catholic tradition and mandates our honor of it: As a consequence of the basic human right of participation in self-governance, all Catholics have the right to a voice in decisions that affect them, including the choosing of their leaders, and a duty to exercise those rights responsibly [xii].

We can be easily distracted from the treasure of our Catholic tradition and its witness by the ways of our North American culture of corporate business. Corporate process is composed of a number of people who are used to interview candidates for a position. It is a classic task of a search committee to search through resumes and conduct interviews for the position of executive director or CEO. In this model three candidates are the result of sifting through all applicants. Those three candidates are then presented to the board of directors, who chooses one for the job. This is not our model in the Synodal Catholic Diocese of the Southeast. We are synodal [xiii], which requires that the three voices of laity, clergy and bishop(s) come to consensus in major decisions, such as the choice of Bishop. Our Diocesan Norm 67 calls for a wide vote that includes as many of the faithful as possible to elect a bishop. We need to exercise our right and responsibility to prayerfully discern and name candidates to be considered for the election as our next Bishop. Without your informed and conscientious participation, any process for such will be flawed because it is not faithful to our synodal life in communion with one another. Active participation in the process helps to determine the sensus fidelium [xiv] of our Diocese and its communion with others. Let the people speak!

We are best a Local Church when all three voices of our synodal life are speaking and working together. It is then that the Holy Spirit reveals Herself in all that we need to continue on our journey together in communion.

With gratitude to God for you, I remain faithfully yours, in Christ.

_______________________

[i] Constitution 2.2.J.iii

[ii] Acts 1:15-26. Before the election of Matthias "Peter stood in the midst of the believers and spoke to them," and "they proposed two men" (Acts 1:18, and Acts 1:23).

[iii] Acts 6:1-6. In regard to the election of Stephen, "The twelve gathered all the disciples together" and instructed them to "choose seven men from among you full of the Spirit and of wisdom." "What they [the twelve] said pleased the whole community..." (Acts 6:2,3,5)

[iv] 1 Timothy 3:1-7; 5:17-19

[v] Titus1:5-9

[vi] Epistle 67

[vii] Epistle 67.3

[viii] Epistle 55.8. Cyprian understood the electoral process to include four dynamic components: the "judicium" (judgment: choice or selection of candidates), the "testimonium" (testimony about the worthiness of candidates), the "suffragium" or election, and the "consensus," or acceptance. The "judicium Dei" (judgment of God) required both the "judgment of the bishops" and the "judgment of all." (Fitzgerald, 1998)

[ix] Epistolae 4.5, PL 50:434-35

[x] Epistolae 10.6 PL 54:634

[xi] Epistolae 14.5, PL 54:673

[xii] Constitution 1.12.B.vi

[xiii] Constitution 4

[xiv] “Sense of the faithful,” an understanding of what the Christian people believe, accept, and reject. It is here, the sensus fidelium, wherein resides the promise of Christ to protect us from error with the guidance of the Spirit. Bishops have taught what to believe, accept, and reject, but always with acceptance or a corrective response by theologians and the faithful even from the very beginning. (Acts 15)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed